The controversial John Breckinridge Castleman statue is officially coming down, so last week, we asked what, if anything, you’d like to see installed in its place.

So far, over 100 of you have responded — and some common themes have started to emerge. One of those is a desire to see some kind of Native American imagery represented, since the statue serves as a sort of unofficial entrance to Cherokee Park.

One listener wrote: “Why not create a recognition of native peoples? Perhaps Cherokee, or some kind of recognition of the over half dozen tribes that had a historical presence in our beautiful state. It should be grand in scale and celebratory. With Daniel Boone at the end of Eastern Parkway, that addition would be both historically appropriate and culturally unifying.”

Another suggested: “A Native American riding a horse, heading toward Cherokee Park. Our major parks are named for native tribes but I don’t know of any statues representing them.”

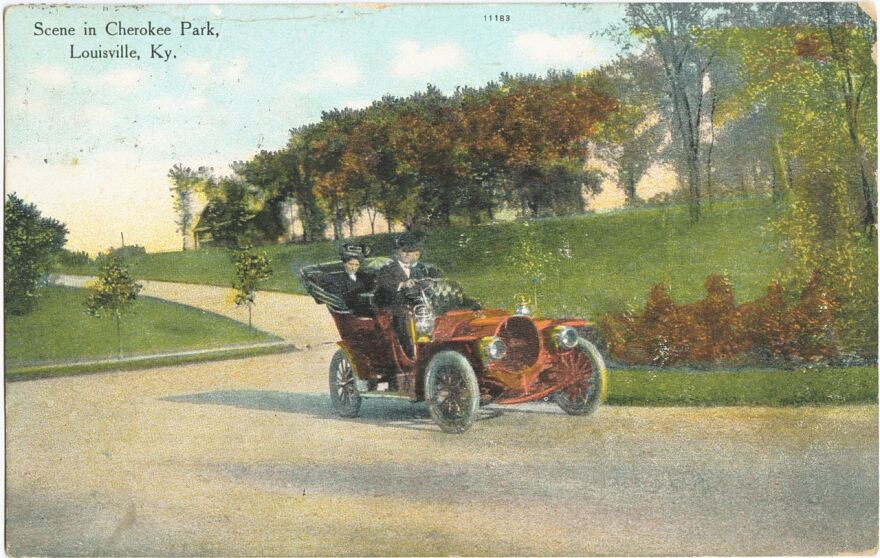

And it’s true: of the 18 Frederick Law Olmsted-designed parks in Louisville, six are named for Native American tribes (Algonquin, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Iroquois, Seneca and Shawnee).

But what inspired Olmsted to name the parks in this manner?

According to Layla George, the president and CEO of the Olmsted Parks Conservancy, there’s no single reason recorded. But understanding the cultural ideals of Olmsted's time, as well as his professional history, allows us to make some guesses. (See editor's note at the end of this story.)

“One of the things is that maybe that period of time — the late 19th century — that Louisville was free to entertain a more romanticized view of Native Americans because, of course, the white culture had ‘triumphed’ at that time,” said George, who previously worked at Louisville Public Media. “At the same time these parks were landscaped, they were being viewed as this unspoiled antidote to the dirty, urban era at that time.”

The city of Louisville, George said, was incredibly polluted when Olmsted was designing the parks in the late 1800s. Coal was the primary source of energy and there was no sewer system or trash pick-up. The parks served as a stark, natural contrast — and perhaps, in Olmsted’s mind, hearkened back to how the land would have looked before industrialization and colonization.

This ties into Olmsted’s legacy as not just a park designer, but a conservationist.

“There was maybe also this idea that these Native Americans had this sort of rugged survivalist ethic and a love of nature,” George said. “Keeping the land unspoiled — so that was part of the reasoning behind the naming.”

Olmsted personally designed Cherokee, Iroquois, and Shawnee parks. Later, his sons and their firm would help develop more parks in Louisville — and many of them continued the naming tradition.

Editor's note: This post originally said that Olmsted personally named Cherokee, Seneca and Iroquois Parks. The article has been edited to include new information: after it was originally published, a listener contacted us with additional research on the subject. He pointed to a series of articles written by the Louisville Courier-Journal in 1891 outlining the naming process and votes by the Board of Park Commissioners on the parks' names. An editorial in an April 1891 issue urged the Board of Park Commissioners to preserve “Indian names in our parks.” Later that year, the commissioners approved the names Cherokee, Seneca and Iroquois.